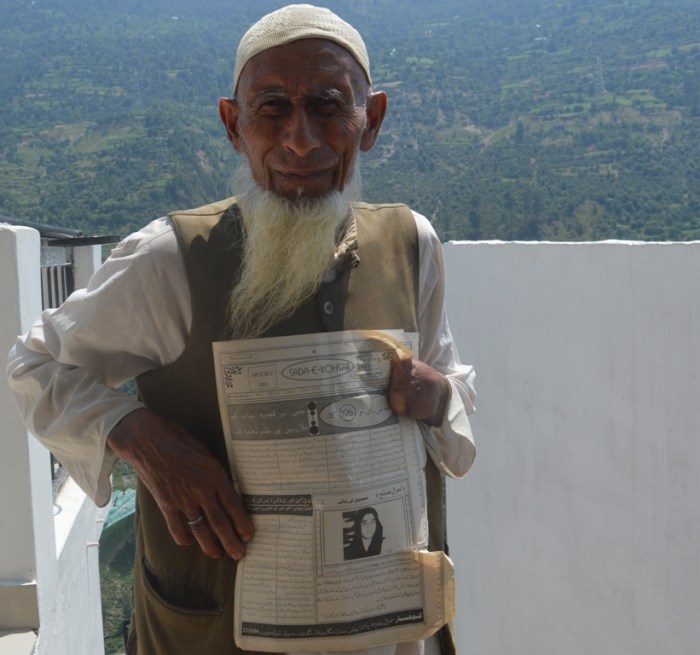

Doda (Jammu and Kashmir): Inside the dilapidated single story mud house with wood and polyethene sheets covering the roof, Ghulam Mohammad Butt, 88 opens his steel trunk and brings out an old, torn newspaper. Flipping all the pages, he stops at the last and keeps gazing at the passport size, black and white photograph printed on the Urdu newspaper.

“She was my 16-year-old daughter,” he suddenly takes off his gaze from the newspaper and says. “She was kidnapped by the Army men with the help of two local Special Police Officers (SPOs),” he adds.

A resident of Village Dhar, Dhandal in Kastigarh Tehsil of Doda district, Ghulam is a living witness of the ruthlessness with which security forces exercised their control in this erstwhile district of Jammu and Kashmir when militancy was at its peak in the region.

A thin man with an amputated left hand, sporting a white beard, a white skull cap with a brown waistcoat over a torn white Kurta, Ghulam a cattle herder spends most of his time reading the same local Urdu weekly newspaper, “Sada-e-Kohsar” published on April 22, 2003.

“Her name was Mumtaza. She had finished her 10th standard in the early months of 2000,” says Ghulam. Mumtaza used to track the mountains in her village for an hour to reach her school in Kastigarh. She was obsessed with learning the English language and had dreamt of becoming a teacher one day.

On a hot summer’s day of June 3, 2000, Ghulam a father of four boys and four girls started his journey with his two sons Hanief and Bhaktawar on foot to a distant forest to graze their herd. Back home, Mumtaza Banoo, then 16, and Farida Banoo, 19 stayed with their mother, Zoona Begum to look after the house.

“My two sons were studying in an Islamic seminary in Gujarat and other two daughters were married and living separately in distant villages,” Ghulam says.

The Same day late in the afternoon, two local SPO personnel along with army men from 10 Rashtriya Rifles (RR) came on routine patrol. While passing by their house, the army men pumped bullets in their two dogs, killing them instantly.

“Mumtaza and Farida were crying as to why they killed our dogs,” recalls Zoona. “When I asked them why they killed our dogs, the army personnel said that whenever they used to pass from our village, the dogs used to bark at them giving enough time to militants to flee the area.”

The three family members spent their night grieving over the killing of their two dogs, not knowing that the worst was yet to come. On June 4, 2000, as Ghulam and his two sons were still deep inside the woods with their herd, the family members back home were enduring the worst.

As the hour needle struck 11 pm, the sounds of jackboots rented the air as if there was a search operation going on in the village.

Suddenly, a huge bang on the door made Zoona restless.

“We didn’t open the door and suddenly they barged from inside the window after breaking the iron grills and started dragging my daughter Mumtaz. Me and Farida caught her legs, so that they can’t pull her out. But our strength was outnumbered in front of their strength,” she recalls.

Zoona still remembers, how her daughter was crying and sobbing, asking her tormentors to leave her. “But they disappeared with her in the dead of the night,” she says.

It was the last time anyone had seen or heard about Mumtaz. A messenger was immediately sent to Ghulam to convey the message about the abduction. The message reached him late and he was only able to reach back on the seventh day and straight away traveled further to district headquarters Doda to file an First Information Report (FIR).

In the FIR he mentioned the name of two local SPOs who worked as informants to the local army unit stationed at Kastigarh. “I mentioned the name of two local SPO’s who were identified by my daughter and wife.”

As soon as he emerged out of the police station, some army men bundled him into a gypsy and drove him straight to the office of an army commander in the police lines of Doda Town.

“The Commanding officer of the army unit asked his second in charge to take me to the Superintendent of Police (SP), Doda,” recalls Ghulam. “There was a Sikh SP who spoke Kashmiri language well and offered me Rs 6 lakh and jobs for two family members if I take my case back. But I declined his offer and asked for my daughter dead or alive. When I was adamant on my stand, he shunted me out of his office. ”

Since then, the case registered at the police station never progressed even though the poor, old man was made to make numerous rounds of the station. “Every time I visited them, they used to ask me to bring witnesses. That time only my daughter and her mother was present. Was it my job to search for the witness or theirs?” he asks.

A year after Mumtaz’s disappearance, her elder sister, Farida then 19, who had seen her being taken away by the forces died due to cardiac arrest. “She couldn’t bear separation from her younger sister and died,” says Ghulam amid tears.

For him, the quest for justice will never end. He took the case to Jammu and Kashmir State Human Rights Commission (JKSHRC), Srinagar a few months after the abduction, where after few hearings the Chairman of the Commission changed, putting a grinding halt to the case. He then moved to Crime Branch, Jammu, where again the officials asked him to come up with the witnesses. “I had to sell my cattle to finance my travel to Jammu and Srinagar to follow up the case. What I still wanted to hear is whether my daughter is dead or alive?”

Back home, Mumtaz’s six siblings and mother still believe that their daughter may be still alive. But Ghulam fears the worst, “I know that they have killed her the very same year and I don’t want their blood money,” he says after a deep pause.

“What I still want is that if she is dead then they show me her grave, so that I can assure myself that I have her dead resting peacefully below the earth and if alive then bring back her to us,” he adds.